In Insight Meditation, investigation of our experiences in each moment as they present themselves to us through our six senses (five sense and mind in Buddhism) is key to developing insight and liberation. So we investigate it all - sights, sounds, bodily sensations, smells, tastes, and mental arisings which encompasses every mental and emotional experience we have, thoughts, feelings, moods, mind states, memories, fantasies, projections, and on and on…

Every single one of these experiences has three characteristics - impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and not self. This writing will concentrate on impermanence bringing in an introduction by Normal Fischer, poet, essayist, and Soto Zen Buddhist priest, and a deeper exploration by Andrew Olendzki, Buddhist scholar, author, practitioner, and professor at Lesley University and the director of its graduate program in Mindfulness Studies.

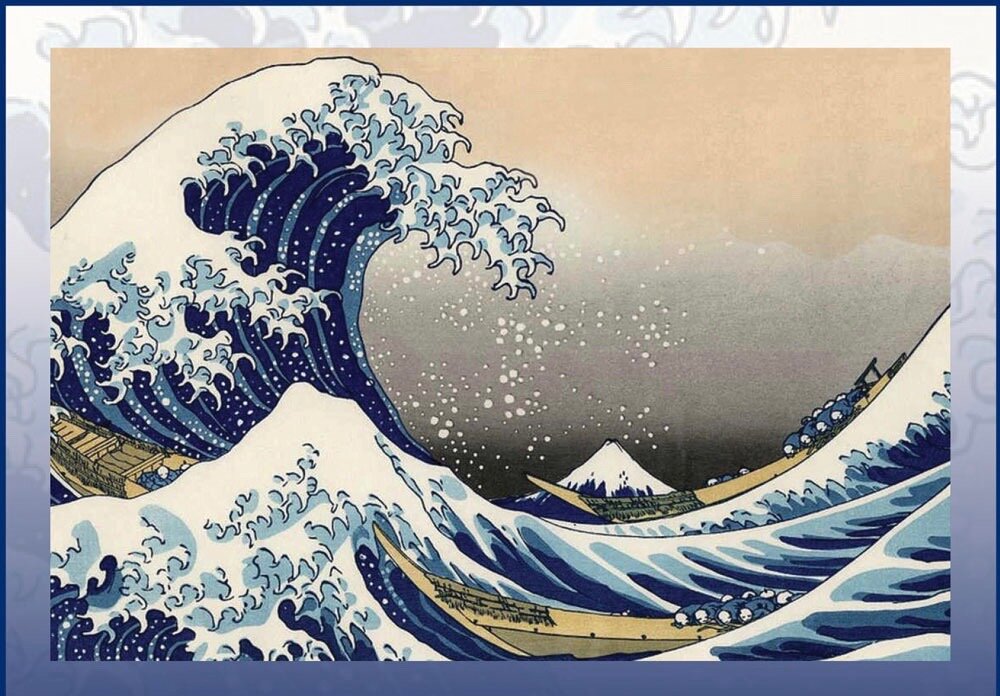

We all have some understanding of impermanence. The evidence is all around us. Breezes arise, get stronger, cease, begin again. The sun rises, passes through the sky, and sets. Our hearts beat and pause, beat and pause. New Year’s Eve marks the passing of another year, the beginning of another.

As Norman Fischer points out in his Lion’s Roar article “Impermanence is Buddha Nature,” "Practitioners have always understood impermance as the cornerstone of Buddhist teachings and practice. All that exists is impermanent; nothing lasts. Therefore nothing can be grasped or held onto. When we don’t fully appreciate this simple but profound truth we suffer, as did the monks who descended into misery and despair at the Buddha’s passing. When we do, we have real peace and understanding, as did the monks who remained fully mindful and calm.

As far as classical Buddhism is concerned, impermanence is the number one inescapable, and essentially painful, fact of life. It is the singular existential problem that the whole edifice of Buddhist practice is meant to address. To understand impermanence at the deepest possible level (we all understand it at superficial levels), and to merge with it fully, is the whole of the Buddhist path. The Buddha’s final words express this: Impermanence is inescapable. Everything vanishes. Therefore there is nothing more important than continuing the path with diligence. All other options either deny or short-shrift the problem."

Andy Olensky invites us to share in his exploration of impermanence, anicca**

"Let’s start by recognizing the roots of this word, anicca. Like many other important words in the Buddhist vocabulary, it’s constructed as a negative. The prefix “a-” reverses its meaning, and what is negated is the term nitya in Sanskrit or nicca in the Pali spelling (the two languages are very similar). This word nicca means everlasting, eternal, unchanging. In what sense was the word “permanent” being used in ancient India? What exactly were the Buddhists negating?

In the intellectual environment in which Buddhism evolved, the concept of something being stable and lasting was very important. Many religious traditions of the world take this view: clearly the world of human experiences is constantly changing, the data of the senses and all they reveal is in constant flux, but underlying all this change surely there must be something stable, something that it all rests upon…

This idea works on both the micro-cosmic and the macro-cosmic level. There is a sense that all the way out there, at the very limit of this world or world system, there is something permanent (nitya) from which this world emerged—Brahman or God. And all the way in here, deep in the innermost world, there is also something stable—the soul or Self. In the profound mystical intuition of the Upanishads these two are not separate, but are two manifestations of the same reality....

This is the background against which Buddhism was working. And the Buddha, with his several excursions into the nature of human experience, basically came to the conclusion that this is an entirely constructed concept. The claim of stability articulated in these traditions is really just an idea that we project onto our world; it is not to be found in actual experience. So one of the principle insights of the whole Buddhist tradition is that the entire world of our experience—whether the macro-cosmic material world or the micro-cosmic world of our personal, inner experience—is fundamentally not permanent, not unchanging. Everything is in flux...

Let’s begin by looking at this issue from its broadest perspective, as an idea of change or non-change, then gradually, [moving] from the level of concept to the level of experience, becoming intimate with the details of looking at change in our experience, moment after moment after moment...

A natural feature of all our experience is that it’s accompanied by an affect tone or feeling tone. Everything we experience generally feels pleasant or unpleasant. Sometimes we can’t tell whether it’s one or the other, but that too is a natural part of our sensory apparatus. Unfortunately, because we have this underlying tendency for gratification, we want—we crave—for the pleasurable aspects of our experience to continue. We also have an underlying tendency to avoid pain, and so we yearn for the painful aspects of our experience to stop or to remain unacknowledged. So this force of craving, in both positive (attachment) and negative (aversion) manifestations, arises naturally (though, as we shall see, (not necessarily) from the apparatus of our sensory experience.

The problem is that, when this craving is present in experience, it prevents us from being authentically in the moment. For one thing, this craving impels us to act, and in acting we fuel the process of flowing-on (Samsara). It also prevents us from seeing our experience “as it is,” and inclines us to view it “as we want it to be.” This, of course, contributes to a significant distortion of reality. The wanting itself is the fetter, the tie, the attachment. Because of our wanting to hold onto the pleasure, and our wanting to push away the pain, we are both tied to craving and tied by craving.

You might think of it as a ball and chain that we’re dragging around with us. As long as we’re encumbered by this burden, it is going to influence how we confront each moment’s experience. The intriguing thing about this ball and chain, however, is that it’s not shackled to us—we clutch it voluntarily. We just don’t know any better.

It is important to recognize the way in which these two factors—ignorance and craving—support and reinforce one another. If we understood that the objects we cling to or push away are inherently insubstantial, unsatisfying, and unstable, we would know better than to hang onto them. But we cannot get a clear enough view of these three characteristics, because our perception of the objects is distorted by the force of our wanting them to be the source of security, satisfaction and substance. If we could let go of wanting experience to be one way or another, we could see its essentially empty nature; but we cannot stop wanting, because we don’t understand these things we want so much are ephemeral.

And so we are cloaked in ignorance and tied to craving; and we are also incapable of discerning a beginning or an end to the flowing-on known as saṃsāra. Taken as a whole, this passage is laying out the nature of the human condition and the limitations of our ability to see the impermanence of our own experience. It shows how, from one moment to the next and from one lifetime to the next, we are compelled to move on and on and on, continuing to construct and inhabit our world. And both the beginning and end of the entire process are entirely beyond the capacity of our minds to conceive...

So this passage sets the stage for us…No story is going to help us much in figuring out what we’re doing here. All we have is what is right in front of us, and that is obscured by the ignorance and craving we continue to manifest.

But this is by no means an insignificant starting point. The beginning and end of the process might be unknowable, but we can know what is present to our immediate experience. Since there is no point in wasting energy on speculation about origins or destinies, our attention is best placed on investigating the present and unpacking the forces that keep it all flowing onward. This is really where Buddhism starts and where it thrives—in the present moment. We have no idea how many moments have gone before or how many will yet unfold—either cosmically or individually—but each moment that lies before our gaze is, potentially, infinitely deep.

The critical factor is the quality of our attention. If a moment goes by unnoticed, then it is so short it might not even have occurred. But if we can attend very carefully to its passage, then we can begin to see its nature. The closer we look, the more we see. The more mindful we can be, the more depth reality holds for us.

The Buddhist tradition points out some of the dynamics of the present moment—its arising and passing away, its interrelatedness to other moments, its constructed qualities, the interdependence of its factors—and then we have to work with it from there. The only place to start is the only place to finish—in this very moment. And that of course is why the experiential dimension to Buddhism—the practice of mindful awareness—is so crucial. You can’t think your way out of this. You just have to be with the arising and passing of experience, and gain as much understanding from the unfolding of the moments as you can.

Step by step, investigated moment by investigated moment, the illusions that obscure things and the desires that distort things will recede as they yield to the advance of insight and understanding. In this direction lies greater clarity and freedom.

**"The Context of Impermanence" (Insight Journal, Fall 1999) https://www.buddhistinquiry.org/article/the-context-of-impermanence/.