We’ve come a long way in exploring the truth of the Buddha’s teachings. And now we’ve come to the foundational practice of Vipassana or Insight meditation. In Insight Meditation, as taught at the Insight Meditation Society in Barre MA, Spirit Rock Meditation Center in Woodacre, CA and in hundreds of smaller Insight Meditation centers around the country, and which is one of the foundations of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), the purpose of our practice is to discover the truth of the three marks of existence, the three characteristics that are inherent in every experience we have, every phenomenon we can perceive. These marks or characteristics are impermanence, suffering, and non-self. It is this exploration that leads to wisdom and freedom.

In order to go forward, I want to go back to an email I sent in May 2023 where I quoted at some length from Bhikku Bodhi’s treasure of a book - The Noble Eightfold Path - Way to the End of Suffering. I often find it uplifting to read some of the teachings multiple times. This quotation is one such teaching.

According to Wikipedia, "Bhikkhu Bodhi, born Jeffrey Block, is an American Theravada Buddhist monk, ordained in Sri Lanka and currently teaching in the New York and New Jersey area.” He is well-known as an author but also as an editor and translator of Buddhist teachings.

He wrote this in his chapter on mindfulness.

“The Buddha says that the Dhamma, the ultimate truth of things, is directly visible, timeless, calling out to be approached and seen. He says further that it is always available to us, and that the place it is to be realized is within oneself. The ultimate truth, the Dhamma, is not something mysterious and remote, but the truth of our own experience. It can be reached only by understanding our experience, by penetrating it right through to its foundations. This truth, in order to become liberating truth, has to be known directly. It is not enough merely to accept it on faith, to believe it on the authority of books or a teacher, or to think it out through deductions and inferences. It has to be known by insight, grasped and absorbed by a kind of knowing which is also an immediate seeing.

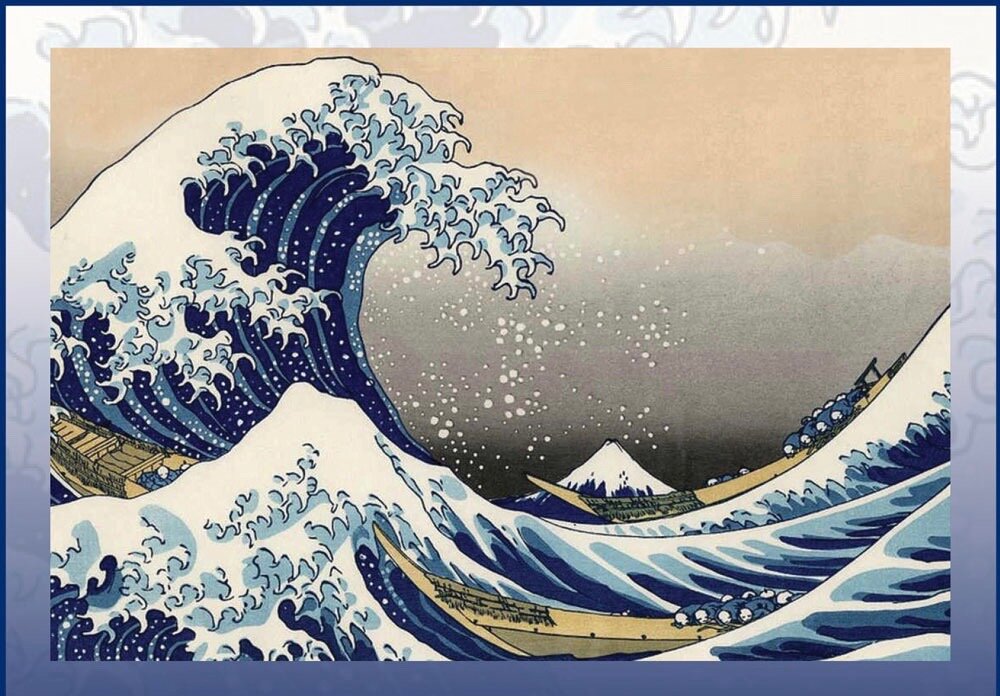

“What brings the field of experience into focus and makes it accessible to insight is the mental faculty called in Pāli sati, usually translated as “mindfulness.” Mindfulness is presence of mind, attentiveness or awareness. Yet the kind of awareness involved in mindfulness differs profoundly from the kind of awareness at work in our usual mode of consciousness. All consciousness involves awareness in the sense of a knowing or experience of an object. But with the practice of mindfulness, awareness is applied at a special pitch. The mind is deliberately kept at the level of bare attention, a detached observation of what is happening within us and around us in the present moment. In the practice of right mindfulness the mind is trained to remain in the present, open, quiet, and alert, contemplating the present event. All judgments and interpretations have to be suspended, or if they occur, just registered and dropped. The task is simply to note whatever comes up just as it is occurring, riding the changes of events in the way a surfer rides the waves on the sea. The whole process is a way of coming back into the present, of standing in the here and now without slipping away, without getting swept away by the tides of distracting thoughts.

“ It might be assumed that we are always aware of the present, but this is a mirage. Only seldom do we become aware of the present in the precise way required by the practice of mindfulness. In ordinary consciousness the mind begins a cognitive process with some impression given in the present, but it does not stay with it. Instead it uses the immediate impression as a springboard for building blocks of mental constructs which remove it from the sheer facticity of the datum (NB: Facticity! Great word!) The cognitive process is generally interpretative. The mind perceives its object free from conceptualization only briefly. (my Italics) Then, immediately after grasping the initial impression, it launches on a course of ideation by which it seeks to interpret the object to itself, to make it intelligible in terms of its own categories and assumptions. To bring this about the mind posits concepts, joins the concepts into constructs - sets of mutually corroborative concepts - then weaves the construct together into complex interpretative schemes. In the end the original direct experience has been overrun by ideation and the presented object appears only dimly through dense layers of ideas and views, like the moon through a layer of clouds.

“The Buddha calls this process of mental construction papañca, “elaboration,” “embellishment,” or “conceptual proliferation.” The elaborations block out the presentational immediacy of phenomena; they let us know the object only “at a distance,” not as it really is. But the elaborations do not only screen cognition; they also serve as a basis for projections. The deluded mind, cloaked in ignorance, projects its own internal constructs outwardly, ascribing them to the object as if they really belonged to it. As a result, what we know as the final object of cognition, what we use as the basis for our values, plans, and actions, is a patchwork product, not the original article. To be sure, the product is not wholly illusion, not sheer fantasy. It takes what is given in immediate experience as its groundwork and raw material, but along with this it includes something else: the embellishments fabricated by the mind.”

It is thought that what occurs in our minds is about 92% our embellishments (I mistakenly wrote this the opposite way round in the original email) which leaves a very small percentage for the raw experience of the original perception. Whether the percentage is correct, it’s clear that a great deal is add-ons, proliferations of our minds made up and scotched-taped on, reflecting what we want, what we don’t want, and otherwise how we are deluded.

"The embellishments fabricated by the mind” are not just random and without purpose. We face a great uncertain certainty in our lives. That which is born will die, that which arises will pass away. This is an inescapable truth and yet we live our lives in the delusion that it won’t happen to us, won’t happen to those we love, won’t happen to things we possess.

The delusions we live with and with which we embellish our experience are the delusions that things are lasting, that happiness can be found in attaining what we want and avoiding what we don’t want, and that there is a solid self to whom all of this is happening. These delusions can be gradually dispelled as we practice. A foundational part of our practice is to see that all experience, all phenomena are impermanent, within each experience is suffering (often the suffering that things are impermanent), and that there is no solid self in any of it, not our bodies, not our minds. These are known as the three marks of existence, or three characteristics of all phenomena - the truths of impermanence, suffering, and non-self.

What may seem counterintuitive is that learning the truth of these teachings is the path to liberation from suffering. In its simplest, least explicable form, if there is not a solid self to whom all of this is happening, there is no one in control, no one creating suffering and no one to suffer. Life unfolds according to causes and conditions, uncomfortable experiences can be held with kind attention as simply the way things are, that good and bad experiences alike are impermanent, are suffering only when we hold on to them, cling to them, and are void of a solid self to whom all of this is happening.

The self in psychology and in Buddhism is a mental fabrication we create over and over again to give ourselves the illusion of that things are permanent, that suffering can be avoided, and that we are in control. Freedom is available to us in the fading of those delusions.

As the Buddha once famously said, For whatever one imagines a thing to be, the truth is ever other than that.

We’ll delve more deeply into these teachings in the coming weeks.